An epic for the digital age

http://edition.cnn.com/2013/09/30/middleeast/gallery/an-epic-for-the-digital-age

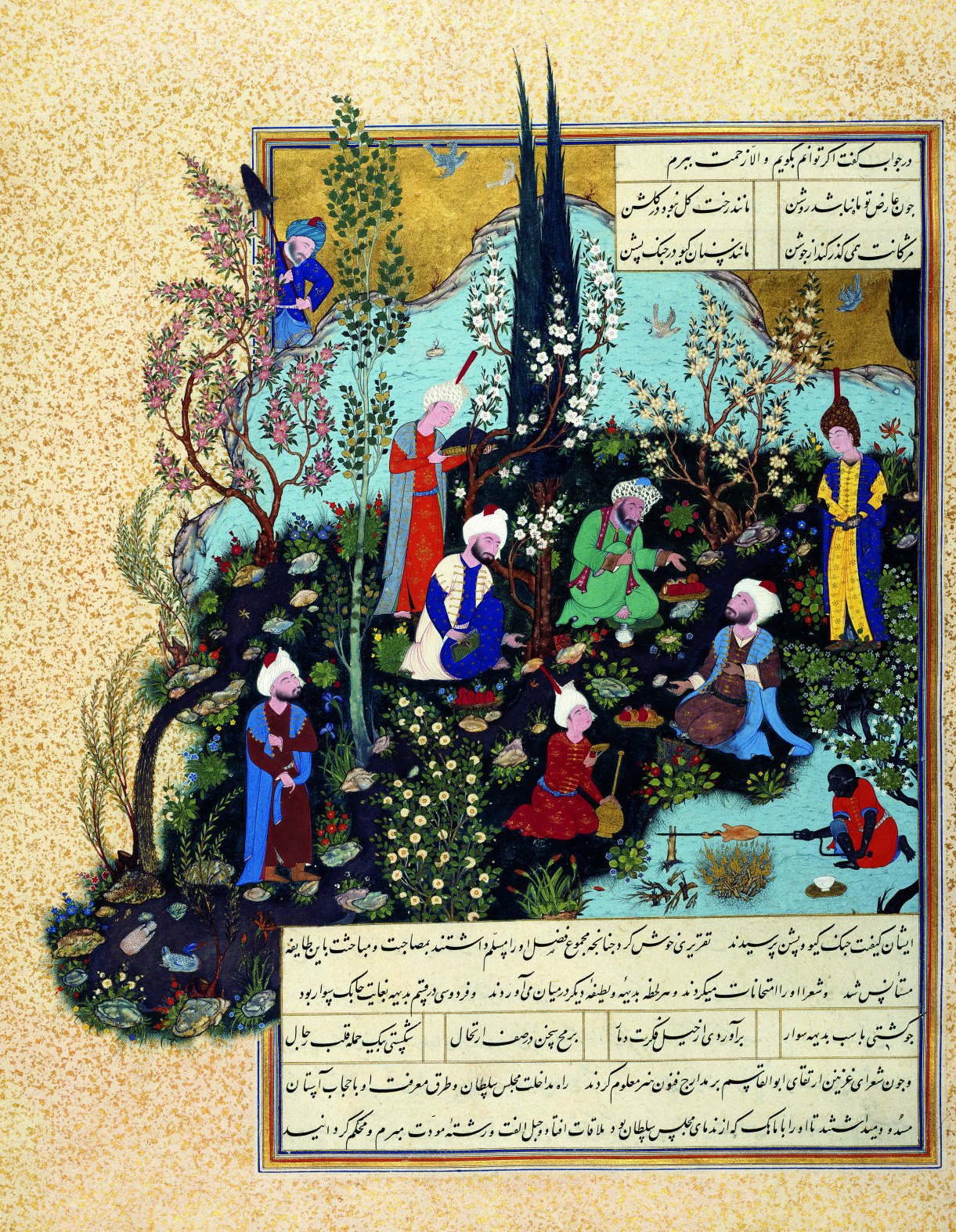

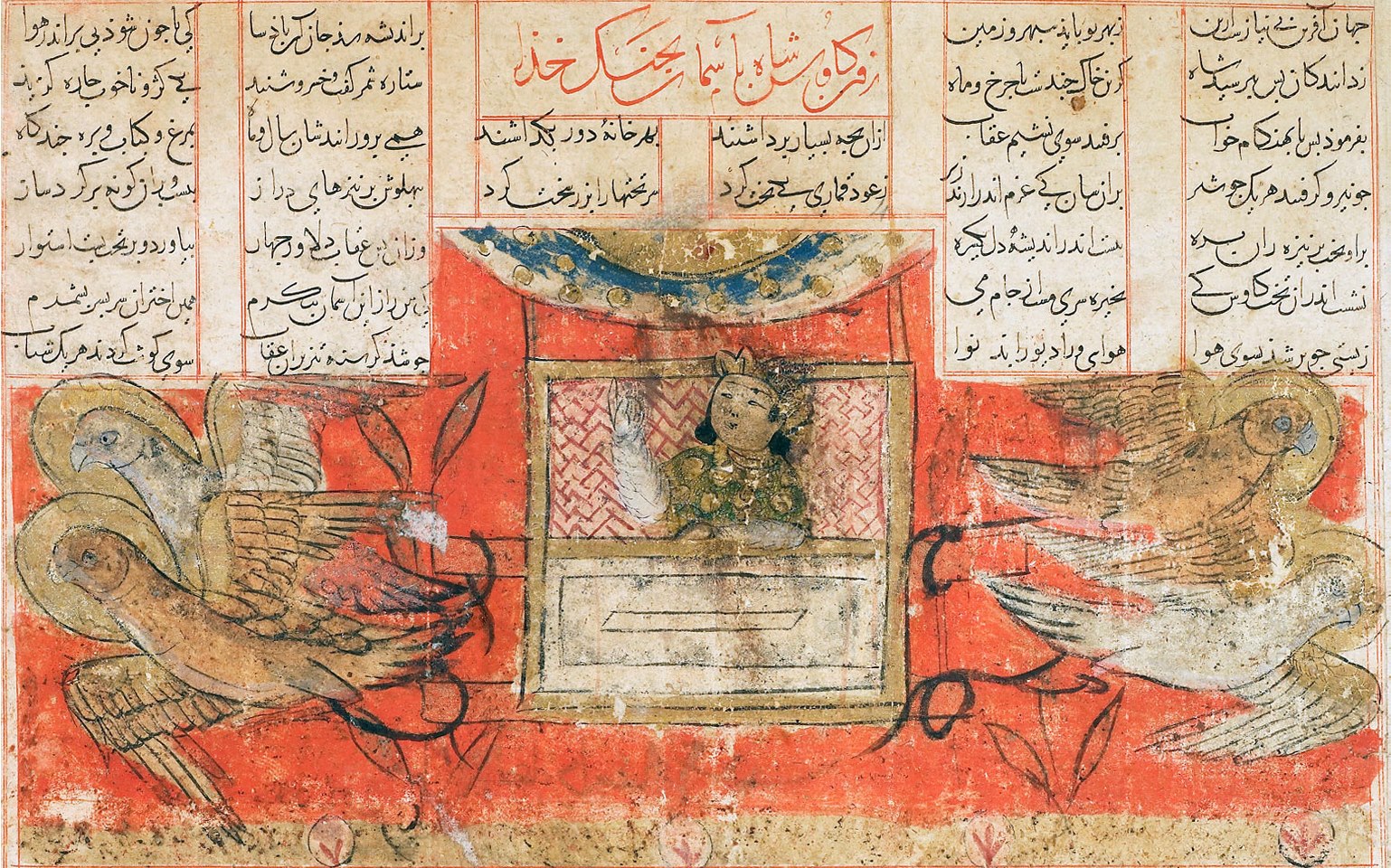

پرواز کیکاوس

Folio From A Shahnama: Shah Kay Kavus Attempts To Fly To HeavenIran

741 H/1341 CE

Opaque water colour, gold and ink on paper

Description

Never a paragon of the perfect ruler, the gullible shah Kay Kavus was tempted by a demon to pursue a preposterous and dangerous plan - to fly to heaven, and conquer the secrets of the celestial spheres. Having considered his options, the king proceeded as follows: he ordered his servants to collect live eagle chicks, and hand-rear them in the palace on fresh meat. Once fully grown, the tame eagles were formidable, “as strong as lions”, and Kavus then ordered his servants to harness four of the birds to a specially-constructed throne, with slabs of raw meat suspended just above the eagles. Next, the foolish king sat into his contraption, and the straining eagles soon had him airborne, as they struggled to reach the dangling food. This is the moment depicted here: hoisted away by the giant birds, Kay Kavus points up in excitement towards the approaching heavens - where the first sphere of the fixed stars or constellations may be seen, with the sun beyond. Eventually of course the birds grew tired, and the king’s upward trajectory came to an end. The plummeting throne crashed to the ground, tipping out the royal passenger in a remote region. He survived the failed adventure, but was greatly humiliated by the contemptuous reproaches of his noblemen when they came to rescue him.

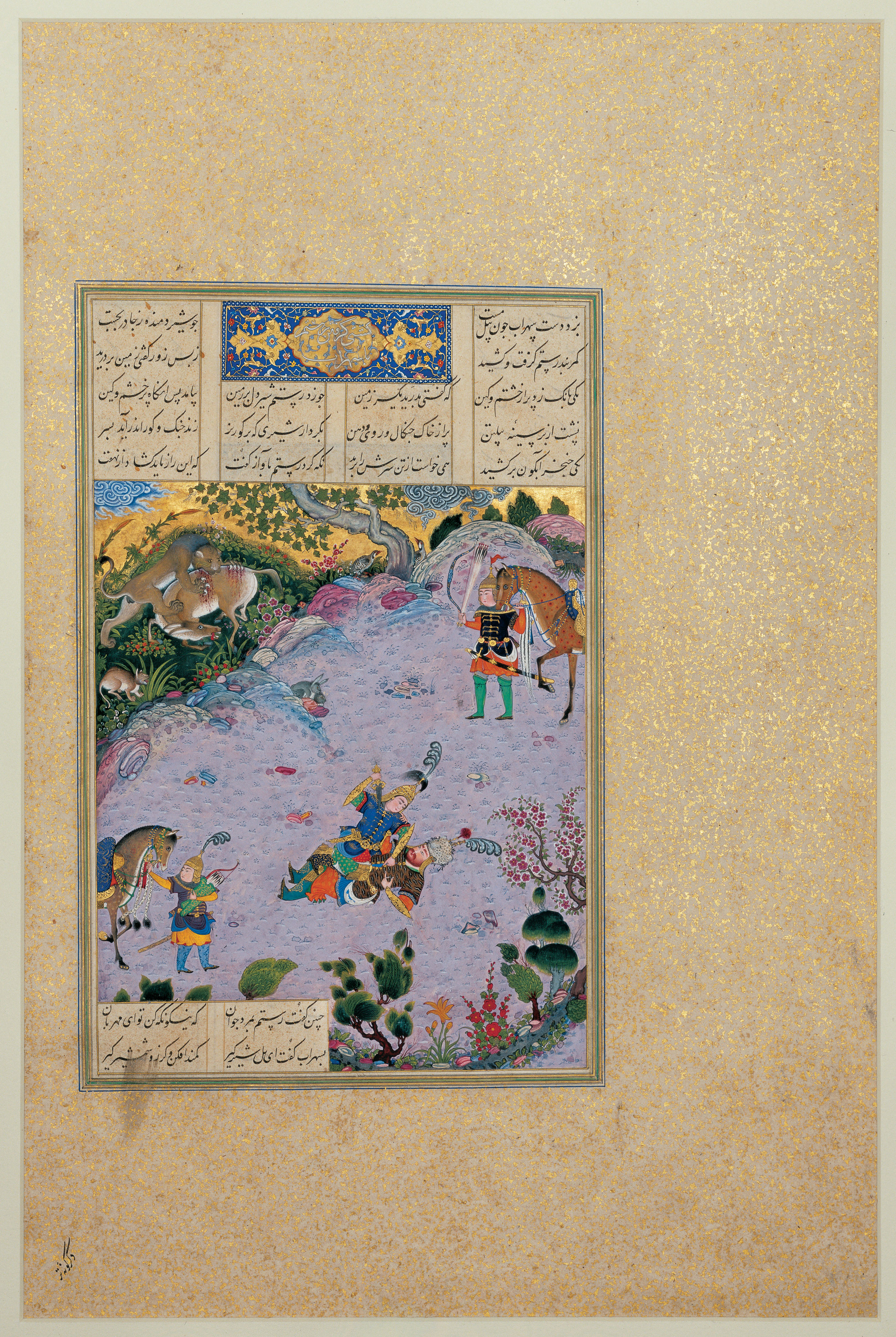

بهرام گور و دختران برزین

Folio from a Shahnama(Book of Kings) by Firdawsi (d.1020); verso: Daughters of Barzin Dance for Bahram Gur; recto: text

1520-1530

Safavid period

Opaque watercolor, ink and gold on paper

H: 30.8 W: 18.0 cm

Shiraz, Ira

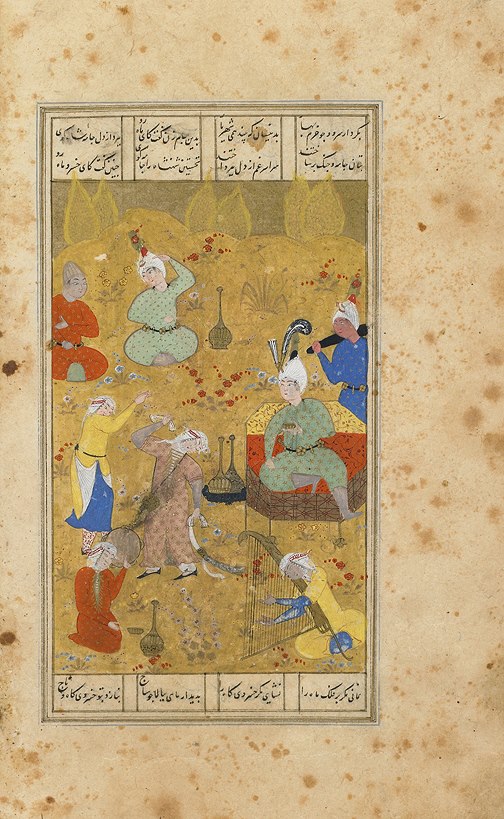

فردوسی

Folio From The Shahnama Of Shah Tahmasp: Firdawsi And The Three Court Poets Of Ghazna

Geography

Iran

Period

Safavid, circa 1532 CE

Dynasty

Safavid

Materials and technique

Watercolour, gold and ink on paper.

Dimensions

Page 47 x 31.8 cm

Description

This illustration is from Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama, one of the most remarkable Persian manuscripts which was started when Shah Tahmasp returned to Tabriz from Herat in 1522 CE. Over a dozen painters, at least two calligraphers, two or more miniaturists, bookbinders, persons responsible for polishing, gold stippling and margin creation, with a whole team of assistants, pooled their talents to design the most sumptuous manuscript ever produced in Iran for a century. In the twentieth century, the manuscript lost its colophon and a large part of the research work done by art historians focused then on the identification of the workshop chiefs and painters. Before it was dismantled in the 1970s, the complete manuscript consisted of 380 folios, including 258 miniatures. The manuscript bears two signatures - of both Mir Musavvir and Dust Muhammad - and a date: 934 H/1527-28 CE. It is thought that two paintings done on thicker paper were added later, between 1535 and 1540, when the manuscript had already been completed (Welch 1979b, pp. 39 et 90). The paintings of this manuscript not only reflect the work of several major painters of the sixteenth century, but also plunge us into the daily Safavid court life. Indeed, although the Shahnama depicts the legendary and pre-Islamic history of Iran, the artists represented the characters in clothing from the period of Shah Tahmasp within their context. In some cases, architecturally decorated objects or elements represented in these miniatures have lasted to this day. The style of the miniatures was the subject of a major study (Dickson and Welch 1981), but the aspects of Safavid court life that these paintings reveal are also worthy of interest. Around 1568 CE, Shah Tahmasp gave the manuscript to the Ottoman sultan Selim II and it remained in the Ottoman royal library until the nineteenth century. It is possible that it returned to Iran in the nineteenth century, but, in 1903 CE, it was sold to Baron Edmond de Rothschild and, in 1959 CE, was bought by the American Arthur A. Houghton, Jr. Today, the two largest parts of the manuscript belong to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and to the Islamic Republic of Iran. Isolated illustrations can be found in many private and public collections in Europe and North America. This illustration shows Firdawsi, the author of the written version of the Shahnama, with the three poets of the court of Mahmud, the sultan of Ghazna, a city which is now in modern-day Afghanistan. Firdawsi left Tus, his native city, in the north-east of Iran, to seek out the patronage of the sultan for his Shahnama. Before meeting with the sultan, he was confronted by three poets of the court who cornered him before finally acknowledging his superior talent. In this miniature painting, a small black servant roasts a bird on a spit while young fine-faced boys bring wine and delicacies to the three Ghazna poets, seated, in the centre of the picture, on the grassy bank of a stream of water. Firdawsi’s isolation is emphasized by his position to the extreme left of the main group, just where the composition spills over into the margin. The role of the young man to the right of the picture, his head elegantly wrapped in a golden turban topped with the Safavid red ‘taj’, is not at once clear, but identifying him is key for the broader interpretation of this illustration and the role of Aqa Mirak in the production of the Shahnama. As a member of the distinguished Sayyid family (recognised descendants of the Prophet Muhammad) of Ispahan, Aqa Mirak was described by Dust Muhammad as being “unique in his time, the confidant of the Shah and unequalled as a painter and portraitist” (Binyon, Wilkinson and Gray 1933, p. 186). Cary Welch has suggested that Shah Tahmasp might have granted his friend the honour of painting the first picture of the manuscript, including Firdawsi, and the three poets of the court of Ghazna. Returning the compliment, Aqa Mirak might have included a portrait of the Shah, the young man in the golden turban in this illustration (Welch 1979b, p. 43). Basing his theory on Tahmasp’s age at the time and the relative youth of Aqa Mirak compared to Sultan Muhammad and Mir Musavvir, the first and second persons responsible for the Shahnama project, Cary Welch dated the picture around 1532 CE, approximately ten years after work on the manuscript began